Volume 2, Number 56 - Thursday, June 20, 2024

Published every Monday and Thursday

Perspective

THERE ARE SO MANY STORIES to be shared about giant sequoias. Among my favorites was first shared by Floyd Leslie Otter in his book, “The Men of Mammoth Forest,” published in May 1963.

Otter died in 1984 at the age of 77, about 15 years after he retired as a forester and manager of Mountain Home Demonstration State Forest. I feel fortunate to have two copies of his book, including #539 of the first edition, signed by the author. The book provides a rich history of what Otter called the North Tule redwoods, giant sequoias growing in the area of the North Fork of the Tule River in Tulare County.

These are the trees that famous naturalist John Muir described in 1875 as “the finest block of the Big Tree forest.”

But the story I’m going to share today is not about Otter or Muir. It’s about a man named Donald “Dude” Sutch and wild times in the Mountain Home giant sequoia grove.

Sutch was born in Pennsylvania in 1903 and living in Springville by the 1910 Census. He died on March 1, 1978, and is buried in Porterville.

As a prelude to Dude Sutch’s story, it’s important to know that early settlers of San Joaquin Valley communities headed to the Sierra Nevada for work and recreation soon after they “discovered” the Big Trees. (Native people were there for thousands of years before, of course).

As William Tweed relates in his “The Story of Balch Park,” published on the Tulare County Treasures website (HERE), a 160-acre parcel that eventually became Balch Park changed hands a few times between the mid-1880s and 1930, when Allan and Janet Balch donated the land to Tulare County for use as a public park.

Today, Balch Park is surrounded by Mountain Home Demonstration State Forest. The state forest is surrounded by Giant Sequoia National Monument, managed by Sequoia National Forest. Otter relates Dude Sutch’s story about how the state of California came to acquire the forest land.

Sutch told Otter that he started in the post-cutting business at Mountain Home in 1929 (this would be the year before the county ended up with Balch Park). Looking for more redwood to use for posts, Sutch tracked down the owner of the surrounding land, a man named Jack Brattin (according to his obituary, Brattin primarily lived in Sanger, Fresno County; from at least 1930 forward, he was in charge of the Hume-Bennett Lumber Company). Brattin gave Sutch permission to cut up the downed redwood on the property.

By sometime in the early 1940s, Brattin wanted to sell the property. I’ll let Otter take over here, telling us what Sutch told him about Brattin:

“He was asking about $700,000 and the U.S. Forest Service wasn’t showing any signs of being willing to meet his price. So Jack figured that some drastic steps were going to be necessary to jar them or the state into action.

“His idea was to mess up the woods by bringing in sawmills. Later he let me and other post-cutters fall green redwoods. The more conspicuous the wreckage, the better. He figured this would get the public riled up enough to force some public outfit to buy the property. And I guess he figured it about right. The Legislature never would have put up the money if we hadn’t made the big noise that we did.

“You see, the Mountain Home country had been left alone for about thirty-five years and people had gotten to thinking of it as a virgin forest. Also, the opening of Balch Park had helped to create an interest in keeping the whole areas as some sort of a park.”

Sutch goes on to describe Brattin’s efforts to influence a public agency to step up to protect Mountain Home and his own work, dynamiting trees and cutting fenceposts.

“I didn’t like to see the big trees go down any better than anyone else. But if I hadn’t cut them someone else would have. I used dynamite by the ton. If they had left me go another five years there wouldn’t have been any good redwood left.”

Sutch also described his process of felling live trees, including one that he described as leaning over a rock pile.

“We thought we would put a line on it and pull it over to one side. The problem was to get the line high up in the tree. So we built a cannon. It held half a whiskey glass of black powder and shot a three-and-a-half-pound wooden arrow with 1,000 feet of carpenter’s cord tied on it. We had a little dog that would wait for each cannon shot and then run and retrieve the arrow. After experimenting and target-shooting with it for a few weeks, we got the cord over the upper part of the tree all right, and then pulled up a light wire with the cord, then a number nine wire, and finally a five-eighths-inch steel line. We cinched that cable around the top of the tree like a lasso on a steer, using a stump puller to tighten it with. We sawed the tree partly off and pulled for two days with that stump-puller but couldn’t budge it. Finally we gave up, blasted it down, and busted it all to pieces on the rocks. So many people were coming up and standing around to watch the job that we were afraid we would break the line and kill somebody.”

In his book, Otter goes on to describe how the state acquired Mountain Home, but that’s a story for another day. (Louise Jackson tells it on the Tulare County Treasures website HERE, accompanied by a video featuring another long-time Mountain Home manager, Dave Dulitz).

But there’s a comment from Otter that belongs here:

“The story of the saving of the Mountain Home redwoods might make an exciting movie if it were told in terms of conservations battling valiantly against ‘ruthless lumber barons’ amidst swinging axes, exploding dynamite and falling trees. The only difficulty is that that wasn’t the way it was.

“The episode might better be described as a campaign to arouse public opinion. Axes, dynamite, and falling redwoods were a part of the strategy, all right, but more sophisticated measures directed through local organizations and the state Legislature brought the final victory.”

Ah, yes, politics and giant sequoias. Also, a story for another day!

• Mountain Home Demonstration State Forest, established in 1946, was the first of the state’s demonstration forests. Managed by CalFire, there are now 14 demonstration forests totaling about 85,000 acres. The forests provide research and demonstration opportunities for natural resources management, along with recreation, wildlife habitat and watershed protection. More information HERE.

Wildfire, water & weather update

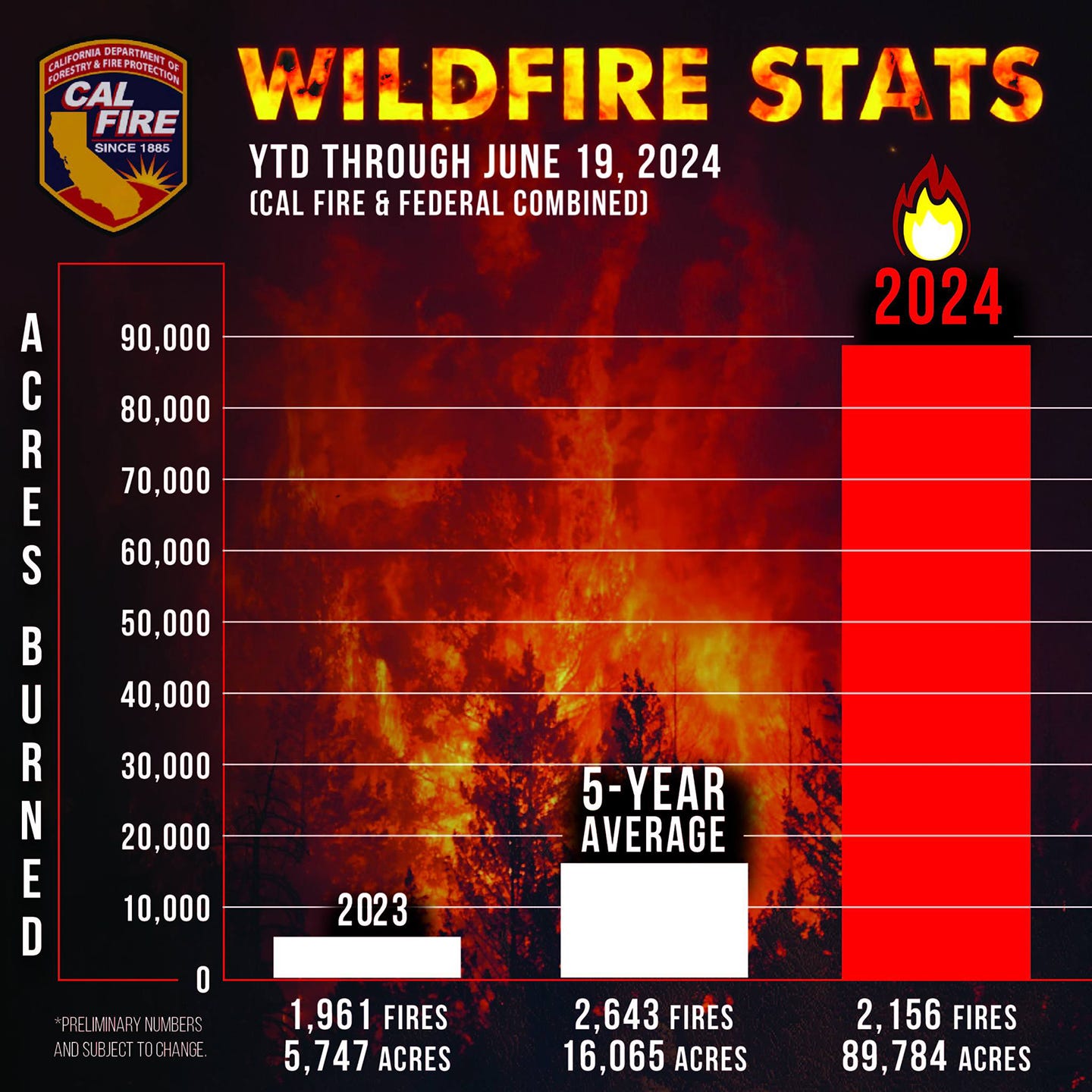

CalFire reports that California is experiencing an active early fire year. The number of wildfires is up 9% this spring, but the acres burned have skyrocketed by 1,462% — from 5,747 acres to 89,784 acres over the same period (Jan. 1 - June 19), which is well above normal for this time of year, the agency reported yesterday.

95% of wildfires in California are human-caused and are occurring in areas with grasses and light flashy fuels that have dried out. Additionally, winds are contributing to these fires moving quickly and consuming thousands of acres.

Heat advisories for the San Joaquin Valley and Sierra Nevada foothills are in the forecasts. The best Sierra Nevada weather forecasts are at NWS Hanford, HERE, and NWS Sacramento, HERE.

Did you know you can comment here?

It’s easy to comment on items in this newsletter. Just scroll down, and you’ll find a comment box. You’re invited to join the conversation!

Thanks for reading!

Used to love reading Floyd Otter's missives in the original Tule River Times...

Hilarious story, what a character was Jack Brattin.