Volume 3, Number 50 - Monday, Feb. 17, 2025

Published every Monday and Thursday

Perspective

LAST THURSDAY I wrote about the WUI — wildland urban interface — and expressed concern that Cal Fire’s effort to identify the severity of the risk of private land adjacent to federal land doesn’t mean much if the federal land isn’t going to be managed to reduce the risk of a wildfire that can be expected to move onto surrounding land.

I always appreciate comments, and reader Evan Frost quickly shared this in response to my opinion:

Yet research has shown the opposite trend — the majority of large and destructive fires (to human infrastructure) actually begin on and move from private land onto public land, not vice versa. See for example Downing et al. 2022, "Public lands are not the primary source of fires that destroyed the most structures." https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-06002-3. So reducing fire hazard on *private lands* in the WUI is actually most important if the goal is to reduce structure losses, etc. Moreover, as has also been shown in many studies, increasingly extreme fire weather, longer fire seasons and growing atmospheric aridity (all related to climate change) are becoming the primary drivers of fire behavior in CA. Without addressing these issues, we cannot expect fire behavior will become less intense or structures less threatened by fire, even with increased fuel reduction. A lot of peer-reviewed science supports this connection, for example https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2018EF001050 and https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab83a7?ftag=MSF0951a18 and https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.2213815120

Frost made many good points.

Although I am not among those who think we always need to add a qualifier that increased wildfire risk is related to climate change, Clay Jordan, superintendent of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (SEKI), said as much when commenting about the loss of so many giant sequoias in wildfires between 2015 and 2021, in an article published HERE in July 2023:

The unprecedented number of giant sequoias lost to fire last year serves as a call to action. We know that climate change is increasing the length and severity of our fire seasons due to hotter temperatures and drought. To combat these emerging threats to our forests, we must come together across agencies. Actions that are good for protecting our forests are also good for protecting our communities.

The NPS article continued:

Managers of lands where giant sequoias occur recognize the importance of working across management boundaries, with each other and numerous other partners, to protect giant sequoias in the face of emerging threats: a warming climate, severe fire, drought, and beetles.

As I’ve reported many times, the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition has provided the infrastructure for that cooperative work. You can read more about it HERE.

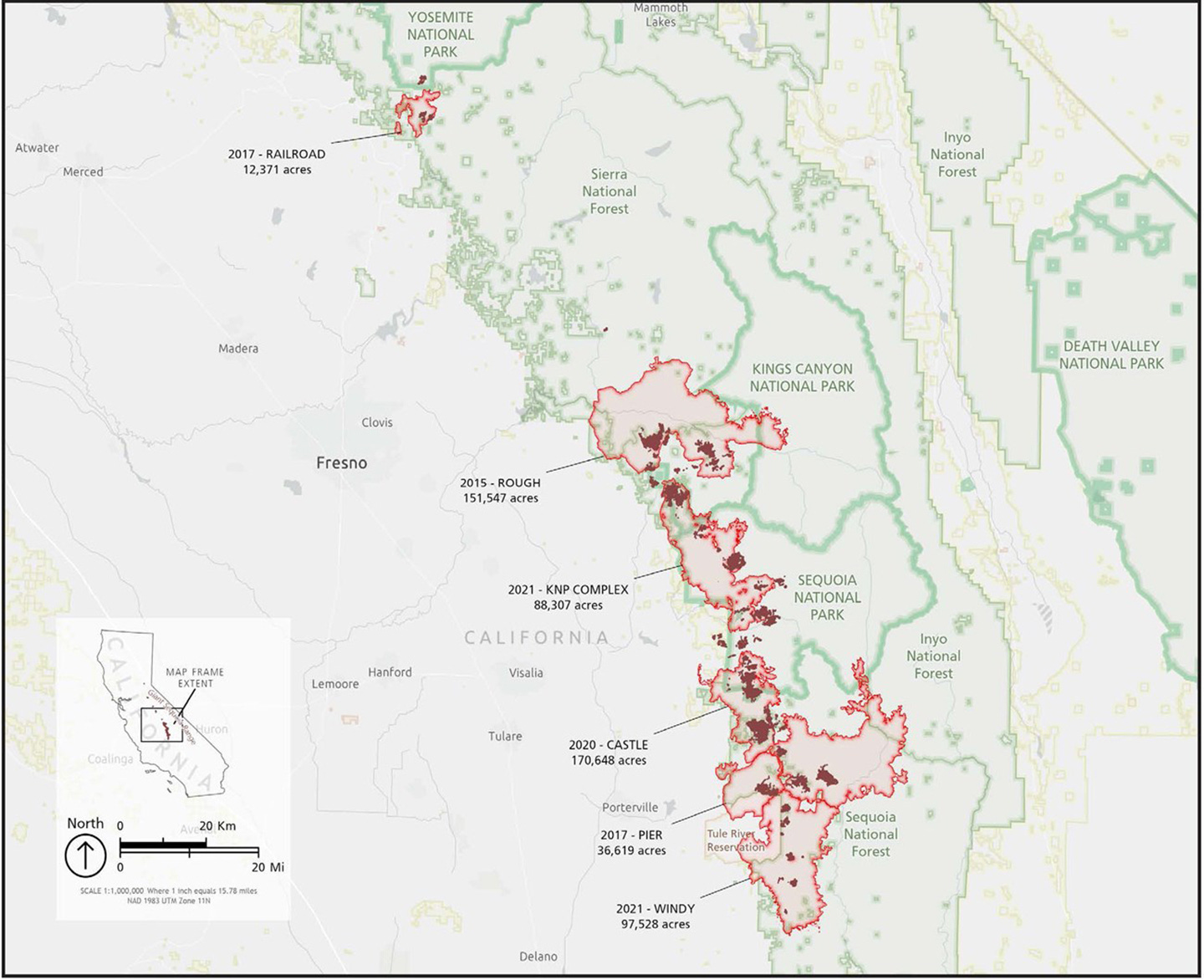

I looked at the six wildfires between 2015 and 2021 referenced in the NPS article HERE (and shown on the map below) and learned:

The 2015 Rough Fire was started by lightning in a remote area of Sierra National Forest.

The 2017 Pier Fire was started in the Tule River Canyon north of Springville. Four people who pushed a burning stolen car into the canyon were ordered to pay $40 million in restitution during their sentencing, as reported HERE. (Fat chance of that, of course).

The 2017 Railroad Fire, covered exceptionally well in Sierra News Online HERE, began along Highway 41 between Sugar Pine and Fish Camp. I think the cause has still not been determined.

The 2020 Castle Fire was also started by lightning. It began in a remote part of Sequoia National Forest and also burned through groves in Sequoia National Forest and other public and private land. More info HERE.

The 2021 KNP Complex was a merger of two of three lightning-caused wildfires that started in a remote area of SEKI. More info HERE.

The 2021 Windy Fire was started during the same lightning storm on the Tule River Reservation near Sequoia National Forest. More info HERE.

So, four of the six fires responsible for killing an unprecedented number of giant sequoia trees were started by lightning on federal lands (I am including the Tule River Reservation because it is federal land held in trust for the sovereign tribe).

I couldn’t tell exactly where the Pier or Railroad Fires started, but because Cal Fire’s online records show the fires as “not Cal Fire incidents,” I’m assuming (never good, I know!) the fires started on federal land. One was clearly human-caused and the other is undetermined.

Might the areas where those two fires be considered part of the WUI, because they were near communities? Maybe.

However, all the research cited by Evan Frost notwithstanding, I remain concerned about the vulnerability of giant sequoia lands — and the risk to nearby communities.

And — in case you wondered — it’s not that I don’t believe the climate is changing. It’s that I often see “climate change” blamed and the presence of extraordinary fuel ignored. A topic for another day.

To answer the question I posted in the headline — I think we need to keep a focus on the wildlands and the WUI.

Wildfire, water & weather update

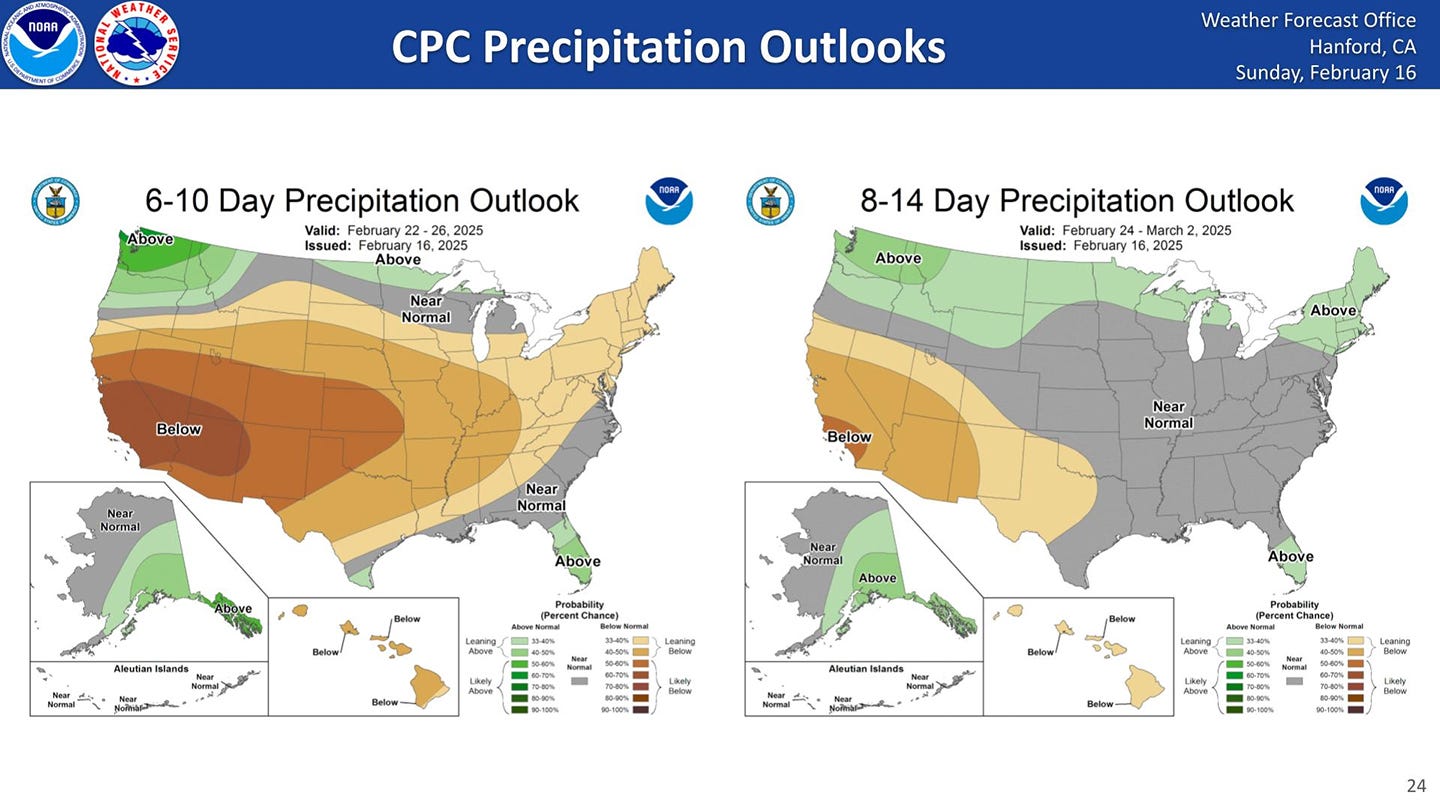

I could see a great distance from the west side of the southern San Joaquin Valley yesterday, and the higher elevations of the Sierra Nevada were white. That was good news. Unfortunately, the bad news is that the National Weather Service is showing that drier conditions are expected through the end of the month.

Could we have a “miracle March” to make up the snowpack? It’s happened before and we can always hope. But past trends show it’s probably about about time for a few years of drought. The California Drought Map (HERE) shows the Sierra Nevada from Mariposa County south in “moderate drought.”

The state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment HERE reports that California has become increasingly dry since 1895 and shows the wide swings between wet and dry periods.

Did you know you can comment here?

It’s easy to comment on items in this newsletter. Just scroll down, and you’ll find a comment box. You’re invited to join the conversation!

Thanks for reading!

I appreciate this discourse ... thanks!

My comment that you included in this post was in response to your stated suggestion that the greatest risk to human communities is from fires that start on federal lands. Looking at a small handful of 6 fires that you listed does not provide evidence one way or another what the trend or magnitude of cross-boundary risk actually is in the southern Sierra. One would need to analyze a large sample of fire starts across many years and all ownerships, and analyze which fires have contributed the most to structure loss. The study that I referenced presents such as analysis across the western states, and found that most fires that burn down structures start on private and not federal land. Of course, regional differences in terms of pvt/public lands fire behavior may exist, but smaller scale analyses that demonstrates this are to my knowledge not available.

What we can say is that the risk of fires moving from federal to private land (and vice versa) is often site-specific and varies widely depending on local terrain, vegetation types, location/size of WUI, etc. Irrespective of these issues, the scientific and real-world evidence is very clear that the most effective way to mitigate fire risk to communities (if this is our goal) is by reducing fuels *immediately around* communities, rather than in much more remote 'wildland' areas. For example refer to USFS researcher Jack Cohen's large volume of work, and there are many studies that support his findings, such as https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-5776626/v1

The risk of wildfire to sequoias is another issue altogether, and not directly related to issues about structure and community loss. Since the groves are all on federal land, they are likely more at risk from fires that start on nearby (usually federal) land, so fire/fuels management to help safeguard the groves should necessarily take place in and adjacent to these forests.

Lastly, your apparent lack of interest in recognizing climate change as a primary factor contributing to increased fire risk for communiities and sequoias (at least that was my impression from your piece) is a common problem -- most people want to point to one or maybe two things for why the fire situation has changed so dramatically in California, but refuse to recognize other factors that are equally if not more involved. Of course the answer is that *numerous, interacting factors* are together responsible for the wildfire crisis -- it's not just increasing wildland fuels, or WUI development, or more human-caused ignitions, or climate change, or lack of 'good fire' -- but all of them together. To ignore this reality is to oversimplify the situation and can easily lead to action steps that are unlikely to be successful and may not even address the primary factors involved. Hopefully we can all agree that this is a complex, multi-faceted problem that must be addressed simultaneously in a number of different ways and at different scales, if we are ever to make any significant progress.