Volume 3, Number 54 - Monday, April 21, 2025

Published every Monday and Thursday *

Perspective

IT’S BEEN TWO MONTHS since I announced a break in my twice-weekly newsletter schedule, and I’m still not ready to resume that publication schedule.

But last week, I was asked to report on the potential impact President Donald Trump’s executive order about timber production might have on Sequoia National Forest. A few newspapers have published versions of my article, and others are likely to publish soon.

You may know that on March 1, the president ordered expanded timber production (HERE). On April 3, the new Secretary of Agriculture, Brooke Rollins, issued a memorandum (HERE) calling upon the Forest Service to do just that. Her memo designated an “emergency situation” on national forest system lands, including Sequoia National Forest.

I won’t repeat everything in my article, which you can read if you like. My impression is that timber production is unlikely to be reintroduced on the part of SQF that is designated as Giant Sequoia National Monument — at least not anytime soon.

Could the Monument designation be reversed or the land base reduced? There are differing opinions on that question, as noted HERE.

Given the numerous changes in federal operations since the president’s inauguration, I don’t think anyone can really know how things might go.

The article below is the best I could do to provide information.

Update

* On Feb. 24 I announced that I was taking a break from most other reporting and planned to spend as much time as possible to see for myself what might be going on in giant sequoia country. Like many plans, that didn’t work out quite as I hoped. Some changes in my life interfered. I haven’t given up, but I’m also not ready to resume regular publication. Paid subscriptions remain on “pause” with no editions charged against credits. — Claudia Elliott

Sequoia National Forest is home to about half of our native giant sequoia groves — can the president order logging there?

By Claudia Elliott

Giant Sequoia News

ON MARCH 1, President Donald Trump ordered expanded timber production on federal lands, and the new Secretary of Agriculture, Brooke Rollins, on April 3 issued a memorandum calling upon the Forest Service to up the cut.

Rollins’ memorandum calls for increasing timber production and designating an emergency situation on national forest system lands, including Sequoia National Forest.

The Sequoia — commonly referred to as SQF — spans parts of Kern, Tulare and Fresno counties. The national forest once yielded millions of board feet of lumber annually.

A century ago, timber production provided jobs with logging camps in the mountains and lumber mills there and in the San Joaquin Valley to the west. Many factors contributed to the industry’s decline, and by 2002 — according to a 2007 article by Matt Schmidt in the San Joaquin Agricultural Law Review — mills in Johnsondale, Dinuba and Sanger merged with Sierra Forest Products of Terra Bella to become the sole large-scale sawmill operating in the region.

Nationally, Rollins said the Forest Service manages 144 million forested acres in 43 states. She bemoaned the lack of timber production.

“Forest plans identify approximately 43 million acres suitable for timber production,” she added. “Over the last five years, the Forest Service has sold an average of 3 billion board feet annually.”

Rollins has designated an emergency situation on national forest system lands — including SQF. She directed the agency to meet the president’s order to expand timber production by 25% — and authorized what she called emergency actions “to reduce wildfire risk and save American lives and communities.”

Whether SQF will be able to meet that demand remains to be seen.

In addition to the loss of industrial infrastructure, a plethora of laws, regulations and presidential proclamations impact the potential of timber production in the southern Sierra Nevada. And federal funding has never kept up with one of the major threats to the coveted timber — wildfire.

About 40% of SQF has burned since 2015, and thousands of trees killed by wildfire or beetles are standing — or have fallen.

The 1.1 million-acre national forest ranges in elevation from 1,000 feet in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada to over 12,000 feet and shares borders with Sequoia National Park. Giant Sequoia National Monument, created by presidential proclamation 25 years ago, is part of SQF.

All or part of about half of the Sierra Nevada’s giant sequoia groves are under SQF’s jurisdiction.

Two previous presidents — George Bush in 1992 and Bill Clinton in 2000 — issued proclamations that appear to run counter to plans Trump and Rollins may have for logging in SQF.

In July 1992, President George Bush signed a proclamation intended to protect giant sequoia groves on national forests. That protection included an order removing groves on Sequoia, Sierra and Tahoe national forests from production and determining that the land would not be included in the land base used to establish the allowable sale quantities for those national forests.

President Bill Clinton went further on April 15, 2000. His action by proclamation, using powers under the Antiquities Act of 1906, created Giant Sequoia National Monument, removing 327,769 acres of Sequoia National Forest from the timber base. (The current size of the monument is 328,315 acres.)

In an email on April 14, a USDA spokesperson said the Forest Service “stands ready to fulfill the secretary’s vision of productive and resilient national forests outlined in the memorandum. In alignment with the secretary’s direction, we will streamline forest management efforts, reduce burdensome regulations, and grow partnerships to support economic growth and sustainability.

“Active management has long been at the core of Forest Service efforts to address the many challenges faced by the people and communities we serve,” the statement continued. “We will leverage our expertise to support healthy forests, sustainable economies, and rural prosperity for generations to come.”

The Forest Service did not respond to questions about how the Secretary of Agriculture’s directive will impact SQF.

Emergency response

It’s no secret that California’s Sierra Nevada forestland has been ravaged by drought, insect attack and wildfire. Following devastating wildfires that killed thousands of giant sequoias between 2015 and 2021, in July 2022, Forest Service Chief Randy Moore approved an emergency response to implement fuels reduction in 12 giant sequoia groves. He directed the agency to proceed with a variety of activities — including cutting trees.

A lawsuit against the Forest Service filed on July 13, 2023, challenged emergency response on the Sierra National Forest’s Nelder Grove. The agency and the environmental organizations have made many filings in court with no resolution.

The Forest Service, in a filing related to the Nelder Grove case, said on Feb. 13 that the agency “has a strong interest in resolving the cloud of uncertainty surrounding the validity of the 2022 Emergency Response and the agency’s exercise of its regulatory authority under 36 C.F.R. 220.4(b)(2) as the agency continues to face emergent situations in the region.”

On Feb. 28, Judge Jennifer L. Thurston said lack of resources and a heavy criminal case load meant the court would not look at pending motions for 8-10 weeks and encouraged the parties to settle their disagreement.

Moore’s emergency response for giant sequoias and the “emergency situation determination” recently put in play by Rollins have similarities, including — in part — reliance on Title 36 of the United States Code of Federal Regulations. That section of regulations covers parks, forests and public property.

Rollins, in her effort to comply with Trump’s executive order, is relying in part on a Biden-era law.

Although federal projects require compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act, Section 40807 of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provided a variety of tools that allow the Forest Service to speed up projects in emergency situations. The bipartisan IIJA was signed into law by President Joe Biden in November 2021.

Sharon Friedman, founder and editor of The Smokey Wire, a news site for forest and federal lands issues, responded to a query about how Secretary Rollins’ direction might be impacted by other factors, including SQF’s Forest Land Management Plan approved almost two years ago, and the Giant Sequoia National Monument proclamation.

“The way I read it, Section 40807 of IIJA, which gives the secretary authority for Emergency Situation Determination (states that) any authorized emergency action carried out … shall be conducted consistent with the applicable land and resource management plan,” Friedman said.

She added that she found it interesting that under the next section of the IIJA — a section covering a landscape restoration project under the jurisdiction of the chief of the Forest Service and the chief of the Natural Resources Conservation Service — is a “puzzling” list of exclusions.

Eligible activities for the two agencies would reduce the risk of wildfire, protect water quality and supply and improve wildlife habitat for at-risk species.

But exclusions, Friedman noted, include activity “in a wilderness area or designated wilderness study area, in an inventoried roadless area, or on any federal land on which, by Act of Congress or Presidential proclamation, the removal of vegetation is restricted or prohibited; or in an area in which the eligible activity would be inconsistent with the applicable land and resource management plan.”

SQF lands include all or part of six designated wilderness areas and two presidential proclamations have restricted timber harvest.

Whether the “exclusions” cited would mean that efforts to ramp up timber production on SQF would run counter to current law is among many questions to be answered at a time that new direction is coming out of the White House daily. As an example, on April 16, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration redefined the word “harm” as it relates to endangered species. That action is believed to be part of the president’s plan to increase logging, development and drilling by eliminating regulations that slow issuance of permits.

Timber production

Timber production is measured in board feet. A board foot is a piece of wood 1 foot square and 1 inch thick, or its equivalent volume.

According to the Forest Service, building an “average-sized American home of 2,600 square feet” requires approximately 16,400 board feet of lumber.

A review of the forest plan for SQF — officially Forest Land Management Plan — shows the amount of timber production forecast by the agency after a review of lands suitable for timber production and sustainable yield.

The plan — in the works since 2012 — was finalized in May 2023. It replaced a plan approved in 1988.

Gene Rose, journalist and historian, wrote about timber production in his 2004 book, “Giants among the forests, 100 years on the Sequoia National Forest.”

Rose said the 1988 forest land management plan reduced the annual cut on SQF from about 115 million board feet to 97 million. The 1990 mediated settlement agreement — resulting from litigation over the 1990 plan — reduced that figure to 75 million board feet.

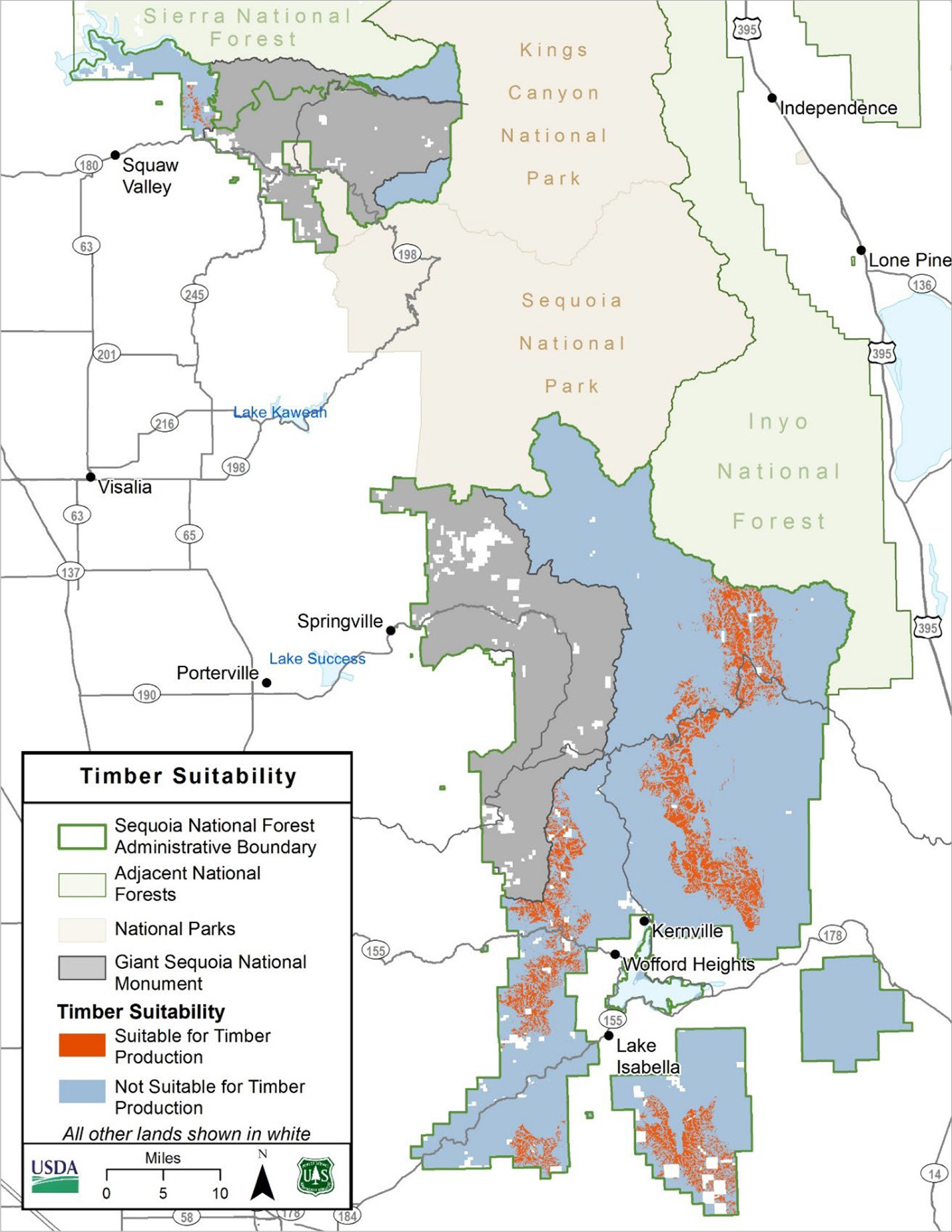

Of 1.1 million acres, only 79,594 acres were determined to be suitable for timber production in the forest plan approved in 2023. The sustained yield limit for the lands that may be suitable for timber production is 159 million cubic feet per decade or 15.9 million cubic feet per year.

Translated into board feet, that is 2.7 to 4 million board feet per year — at the most, enough lumber to build 243 “average” homes yearly.

The Sierra Club, in a statement on April 4, said Rollins’ new policy “puts more than 100 million acres at risk of destruction.” The organization — which has a long history of involvement and litigation with SQF — did not comment on the potential impact specific to SQF.

Approval of the first management plan for Giant Sequoia National Monument, approved in January 2004 — during the George W. Bush administration — was successfully challenged by the Sierra Club and other environmental organizations, and in a separate lawsuit filed by the California Attorney General. In August 2006, a federal judge ruled against the government, writing “The Forest Service’s interest in harvesting timber has trampled the applicable environmental laws.”

In a news release after the 2006 ruling, a spokesperson for the group Earthjustice said the first plan would have allowed 7.5 million board feet of timber to be removed annually from the Monument, enough to fill 1,500 logging trucks each year. This policy would have included logging of healthy trees of any species as big as 30 inches in diameter or more.”

The plan in place today was not finalized until August 2012.

The Forest Service is currently defending a lawsuit brought by the Sierra Club, Earth Island Institute and Sequoia ForestKeeper in early 2024. In that action, the environmental organizations characterize SQF’s restoration projects for land burned in the 2020 Castle Fire and 2021 Windy Fire as logging. The Clinton monument proclamation specifically does not allow logging in the national monument, but does specify that trees can be removed “if clearly needed for ecological restoration and maintenance or public safety.”

In its 2023 forest plan, SQF noted that timber production is the” purposeful growing, tending, harvesting, and regeneration of regulated crops of trees to be cut into logs, bolts, or other round sections for industrial or consumer use.”

But, according to the plan, not just trees from areas designated for timber production can be harvested.

“On lands not suitable for timber production, timber harvest may occur to protect multiple-use values other than timber production, such as for salvage, sanitation, public health, or safety, as specified in plan components for specific categories of lands,” the plan states.

The projected volumes from any salvage or sanitation harvests fluctuate and are not included in the projected timber and wood sale quantities in the forest plan.

Save the Redwoods League, a conservation organization focused on restoring complex forest ecosystems in the coast redwood and giant sequoia ranges, on April 9 said the organization agrees with the USDA “that the nation faces a serious crisis of forest health and wildfire risk — one that the USDA Forest Service is well positioned to address.”

However, the organization found fault with Rollins’ April 4 memo, saying it “problematically blurs the line between ecological restoration, which aims to heal ecosystems, and timber harvest for commercial gain, which prioritizes extraction and profit over long-term forest health.”

Save the Redwoods League acquired the 530-acre Alder Creek property east of Porterville in December 2019, about eight months before the Castle Fire burned through the property. Some of the thousands of large giant sequoia trees killed in that fire were on the Alder Creek property. The League has also worked closely with SQF on restoration projects.

In June 2017, during Trump’s first term as president, the Tulare County Board of Supervisors endorsed his plan to reduce the size of the national monument by over 70%.

According to reporting by KVPR, “the proposal to shrink the monument came from Supervisor Steve Worthley, who used to work in the timber industry. He says the Forest Service isn’t doing a good job managing the monument, increasing the risk of wildfire.”

Voting 3-2, the Tulare County board sent a letter supporting reduction of the national monument to 90,000 acres and opening the rest of the land to other National Forest activities.

On the same day, the Kern County Board of Supervisors declined to take a position on the proposed reduction.

In 2017, Trump reduced the size of two national monuments in Utah but took no action related to Giant Sequoia National Monument.

Save Our Sequoias Act

In 2022 and 2023, similar versions of a bill called the “Save Our Sequoias Act” were introduced in Congress but not passed.

On April 8, Rep. Vince Fong (R-Bakersfield) and Rep. Scott Peters (D-San Diego) introduced the latest version of a Save Our Sequoias bill, H.R. 2709.

Like the 2023 version, the latest effort includes participation of the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition and $205 million in funding over seven years. The Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition, chartered in June 2022, is made up of representatives of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, Yosemite National Park, SQF, Sierra National Forest, Tahoe National Forest, the Bureau of Land Management’s Case Mountain Extensive Recreation Management Area, the Tule River Tribe, Calaveras Big Trees State Park, Mountain Home Demonstration State Forest (California Department of Forestry and Fire Prevention the University of California, Berkeley, stewards of Whitaker’s Research Forest and Tulare County, stewards of Balch Park. The bill also emphasizes collaboration with the state and tribes, with grants available to complete projects.

Environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, opposed previous versions of the “Save Our Sequoias Act,” largely because of provisions to shorten environmental review. The latest version includes language referring to the Biden-era IIJJ and using categorical exclusions to speed up review of projects.

Fong and Peters have been joined by 25 other sponsors in the introduction — 14 are Republicans and 13 are Democrats.

Shine Nieto, chair of the Tule River Tribe, and Kirsten Tobey, interim president and CEO of Save the Redwoods League, expressed support for the bill.

The Tule River Tribe, with giant sequoias on its reservation east of Porterville, is “proud to support passage of the Save Our Sequoias Act,” Nieto said.“The legislation paves the way to formalize a clear path forward on how we can combine our strengths to safeguard the sequoias.”

Tobey said the League welcomes “the opportunity presented by the reintroduction of (the act) to work with Congress to secure the necessary resources and flexibility for our partners to do this critical work, comprehensively and sustainably.”

Information about the bill is online at bit.ly/4lCzHOj.

Did you know you can comment here?

It’s easy to comment on items in this newsletter. Just scroll down, and you’ll find a comment box. You’re invited to join the conversation!

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for all of this, Claudia.It's all very concerning. Along with everything else that's concerning. I have been thinking submitting an article to Mountain Gazette based on my long lost guide to the southern groves. I might need some help but I'm not at that point yet. I very much appreciate your news letters.